The Tiny Home as a Model for Change

Together with a group of students from Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, Dr. Niklas Maak helped develop a prototype of tiny home housing for refugees living in Frankfurt. He wrote about the experience and the tiny home movement for our 2024 print issue: TLmag40: The Ideal Home.

For a long time, the village of Grand Camp in the French department of Morbihan, Brittany, was only known to a handful of people. But that changed when housing in the nearby city of Vannes, as in many cities, became so expensive that the community decided to build a cluster of tiny homes on a former camping site to accommodate the less affluent citizens. So far, seven of a planned twenty-two tiny homes have been built. The former mayor and now senator, Yves Bleuven, hopes to create a model to counteract the housing crisis in rural areas with tenants paying 150 Euros in rent to the community.

The current tiny house movement has many iterations: some people are looking for affordable living space, while others dream of leaving the city and retiring to the countryside. The image of life in a simple hut has haunted the dreams of industrial urban societies since William Cobbetts “Cottage Economy” and Thoreau’s “Walden”, from the German life-reform-movements to the rural hippie communes of the 1960s. In continental Europe, the current tiny house movement is divided into two groups: on one side are the architects and activists including Van Bo Le-Mentzel, whose tiny house, known as the “Co-being house”, questions ideas around a standard comfort of living in times of climate change and social crisis, and uses the tiny house as a laboratory to find out to what extent resource consumption can be reduced. On the other side, a rather escapist leisure-oriented tiny house movement is erecting weekend huts in the countryside near Berlin or in Bavaria.

The German start-up “Raus” offers small cabins for rent throughout Germany’s forests and fields. The name – “out”, in English – says it all: You want be “raus”, out of all the complexities of modern society. The name “Raus” however, also appears in a different context in Germany, namely in connection with migration (“Ausländer raus”). It is interesting to note that in 2015, the year that the first German tiny house manufacturer, Dieter Pugane, an entrepreneur from Rheinau, began his production of ‘Tiny Houses’, and in doing so, created a wave of interest in micro-homes across Germany, a completely different need for small accommodation arose. After Angela Merkel opened Germany’s borders to refugees and made her famous statement “Wir schaffen das” (“We can do it”), there was an urgent need to build a large number of accommodations, for mostly Syrian refugees, in a very short time.

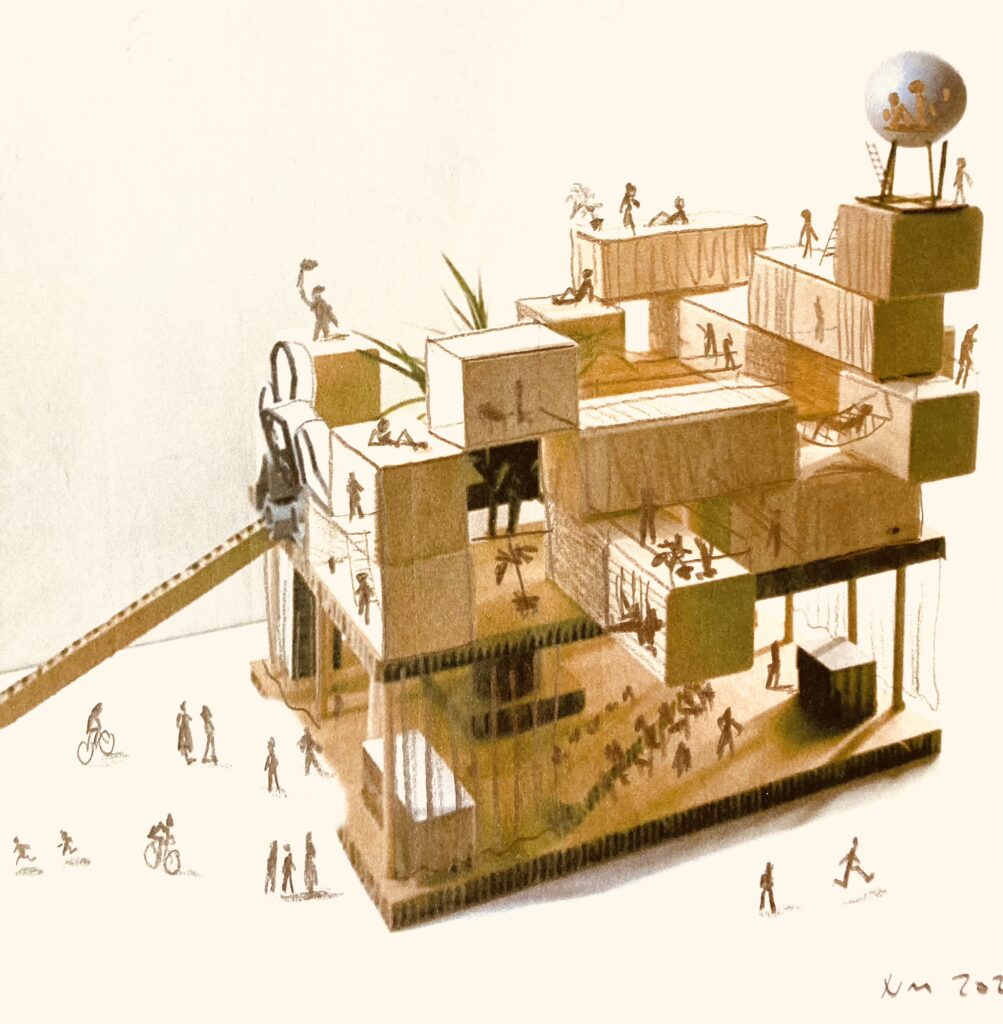

Together with a group of students from Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, we investigated the housing situation of refugees and spoke to numerous people who fled to Germany. One of the main points of criticism was that the refugee accommodation mostly consisted of containers that were placed on the ground and then fenced off for security reasons, aggravating the separation between the new arrivals and the local population. We asked: What if the shelters were placed on stilts, creating a kind of market hall underneath them? What would happen if small residential units, such as containers, were not placed on the ground, but instead raised so that an open space is created underneath, which, if protected with tarpaulins, for example, can be used as a “collective living room” for all those living above, but also as a small theatre or as a “marketplace”; What if the refugees could immediately work in this hall, and open small stores and workshops? Two refugees from Aleppo offered to set up a repair store for cell phones, a baker from Eritrea offered to set up a bakery in a small space, and a shoemaker wanted to repair shoes. Such a place would reverse the narrative: it would not be the refugee who would be a supplicant and recipient of help, but the local community would come and engage the services of the refugees, who would help them with what they needed: their shoes are broken, their cell phone doesn’t work, they are hungry. In this space they would find a solution to all these problems. It would create a personal connection in a normal, everyday exchange. Such a market would be a new meeting space, just as markets are traditionally places where almost everyone likes to spend time.

The principle of the market as a social space of encounter, exchange and rapprochement became the starting point for an architectural project. The students founded a collective called FAM and designed new accommodation typologies for people with limited resources – for refugees, but also for students. They exhibited their designs at the German Architecture Center in Berlin in 2017. Their designs inspired a project at the Städel School in Frankfurt, whose students together with students from the University of Applied Sciences in Frankfurt and biodiversity experts from the Senckenberg Society, spent three years developing the idea of an affordable, ecologically responsible and socially enriching building for students and refugees. The result is The Frankfurt Prototype, an aggregation of tiny homes on stilts: The Frankfurt Prototype is an experimental house for up to 12 residents with a small “market hall” on the first floor. It shows how a young generation imagines the future of living. The Frankfurt Prototype is not intended to be a one-off, but a model for how to build in a more ecologically compatible and socially enriching way and adapt to future needs. This is all the more necessary as construction is in a paradoxical crisis: the influx of people into large cities such as Frankfurt means that more living space needs to be created than ever before; at the same time, as the construction and operation of buildings is responsible for 40 percent of all CO2 emission, as little as possible should be built. So what to do?

A key aim of the prototype is to find out how much space, comfort and privacy people really need for living. Different students show different proposals for different characters – from comparatively luxurious mini-apartments with small green roof terraces to more radical shelters whose residents share kitchens and bathrooms. The aim is to initiate a discussion about standards of cohabitation. The living level is divided into a modular assemblage of roughly container-sized wooden residential units. Thanks to their flexible layout, they allow either space for numerous single units or, if the units are interconnected, new spaces for large families, retirement flatshares and groups of friends or other constellations such as several single parents with their children who want to live together. The Frankfurt Prototype also addresses how construction can be much more resource-efficient in the future. The market hall is built from used steel girders from demolition projects. For the residential cubes above, formwork timber used in the construction of concrete bridges is reused. The entire prototype can be dismantled and transported away without leaving any residue so that it can be reused elsewhere in a new configuration. The infrastructure modules can also be used for the conversion of larger existing buildings, such as the “colonisation” of vacant office buildings and multi-storey parking lots. In this sense, the elements of the prototype are not just prefab architecture, but also a conversion kit. The house is a “breathing bio-machine”. Above this is the “living tower”, a structure in which students live with their self-designed micro-living units, like in a “vertical reef”, and in which, above all, the coexistence of humans, flora and fauna is tested out in a building typology that protects and promotes biodiversity. Life “with, in and as nature”, as Kathrin Böhning-Gaese, Director of the Senckenberg Biodiversity and Climate Research Center, points out. Cooperation with the researchers at the Senckenberg Museum was particularly important for the landscape design that provides shade, insulation and ambient cooling, a habitat for various species and contributes to food production – with “edible walls” – a rainwater treatment system, and façades that provide space for birds and bees.

The Frankfurt Prototype opened in early October, 2024 and is intended to become a platform for public discussions, where students and refugees from Afghanistan, mainly female artists from Kabul’s Centre for Contemporary Art who had to flee after the Taliban seized power, run a café and exhibit their art, and organise a programme of concerts, exhibitions and discussions about the future of the City. The Prototype, though formally similar to tiny house constructions, is not an escapist refuge, but an attempt to reactivate the city in times of crisis with small interventions and become a repair kit for the ruins of office towers, shopping malls, parking lots and other defunct structures now found across the city due to the rise of digital capitalism, with an ever more dominating home office and online retail system.

@frankfurtprototype